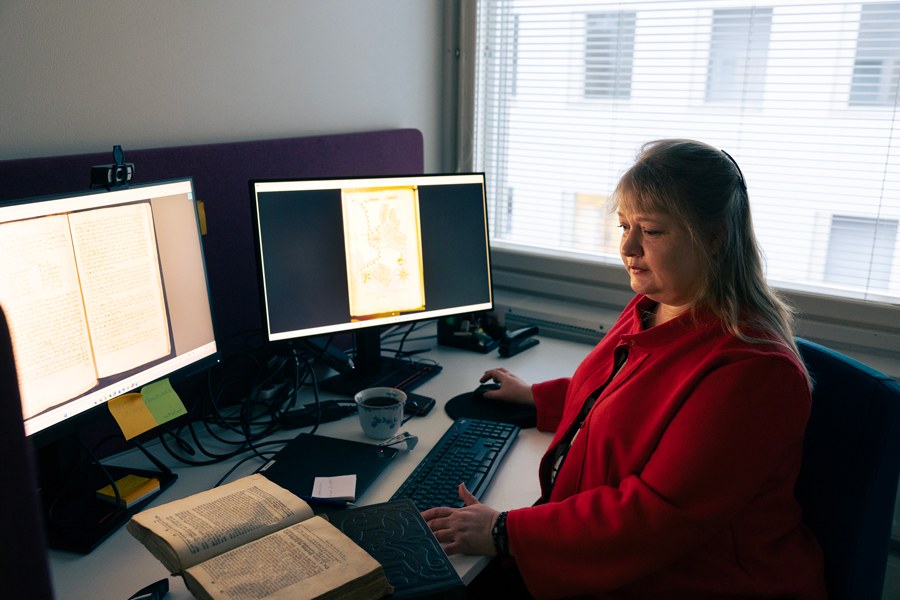

Raisa Toivo sees history as a way to address contemporary challenges

A group of women from Punkalaidun were brought to trial at the end of 1646 for organising a prayer meeting. In court, it was heard how the women had prayed for a neighbour who was going blind. However, in the private farmhouse meeting, they had stretched Lutheranism a bit: after preparing a meal, the women knelt in prayer, striking flint against iron.

Everyday life shapes faith and vice versa

Using the women’s prayer meeting as an example, Raisa Toivo illustrates the lived religion and experiences of rural women in early modern time in a publication of the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters.

“Religion can be studied from many angles. I consider myself a social historian examining the societal manifestations of faith. I examine how everyday life shaped religion and how faith shaped everyday life,” Toivo says.

During the European wars of religion and witch trials, striking flint was not part of the Lutheran practice, and the pastor deemed that an investigation was needed. However, the women from Punkalaidun were not convicted, and the case did not really belong to the district court.

The shared prayer moment created a religious experience that strengthened the village community as people felt they belonged together.

“I would not want to create a dichotomy saying that the church taught things in one way and then people ‘misunderstood’ the teachings in their own way. I am interested in how the interaction between these two – and other parties – creates social change and historical development. People form communities as they live their religion in interaction with others. Sometimes they also limit their communities by acting according to their religious beliefs,” Toivo illustrates.

A researcher of the history of experience aims to identify the social and cultural factors influencing the formation of experiences. A researcher asks, among other things, how experiences are produced, who produces them, and how they are shared. Experiences are most significant in research when they are not individual but shared within communities.

As experiences are evaluated in the community, the process underscores the exercise of power, as not all experiences are equally recognised and shared.

Tracing witch trials and Catholic influence

Professor Toivo has studied the experience of religion and religious conflicts, and the history of family, gender, and violence. Her research topics have always been connected to the history of witches and witch trials in some way. Through them, Toivo has examined, for example, the exercise of power, gossip, and gender in the early modern period.

In her dissertation, Toivo conducted a longitudinal study of the lives of people involved in witch trials.

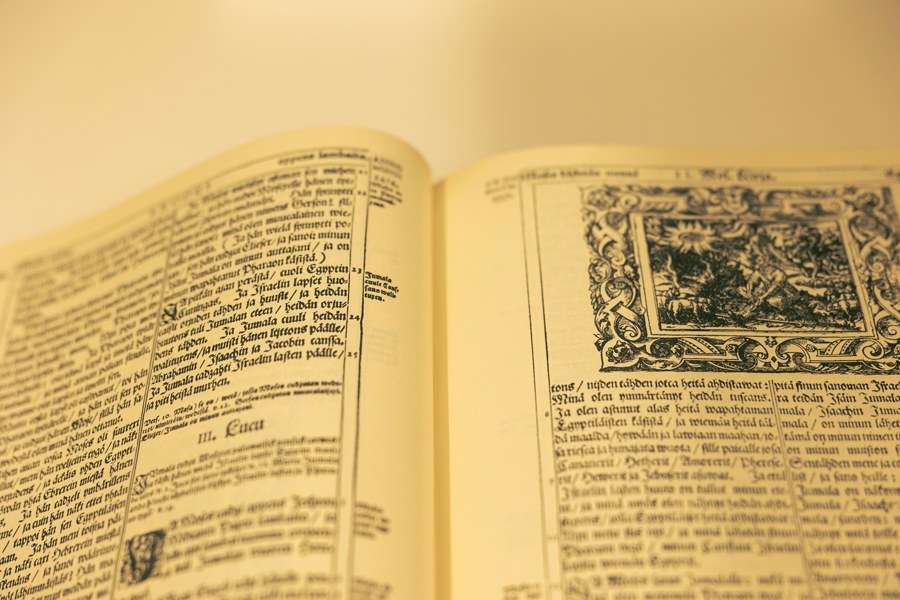

While reading court records, Toivo noticed that although they lived in a Protestant state supported by the Lutheran church, Catholic prayer beads, field blessings, and appeals to saints appeared in legal sources throughout the 1600s. The Reformation, which separated Sweden from the Catholic Church, had already begun in the 1520s under state leadership.

“But new Catholic influence, which spread across Europe during the Catholic Reformation or Counter-Reformation, was felt in even Finland’s Häme region. Some Catholic traditions can still be seen in sources from the late 1600s. Similarly, Orthodox influence is also visible, in e.g., cemeteries," Toivo explains.

Efforts to avoid persecution

Professor Toivo is at home with reading court records and old Swedish, which we can access digitally via the National Archives’ online service. To draw conclusions from sources, a historian must understand the living conditions of the time and concepts that differ from those of today. When writing research, the world of the past must be presented in a way that is understandable and relevant to the modern reader.

“I used to read court records extensively as a method, regardless of whether I used them as material for my research. Context comes from research literature but also from reading sources, of which court records are an incredibly diverse example. They provide many perspectives on the lives of people in the past and are even amusing to read. Court records offer exciting glimpses into the society of their time and the experiences of people in early modern times,” Professor Toivo explains.

A Research Council of Finland-funded project, which Toivo is leading, studies methods of deterring witch hunts. In Finland, witch trials occurred relatively late in the second half of the 1600s, and according to Toivo, there were surprisingly many court cases.

The research is based on the observation that the trials did not turn into actual witch hunts, even though the preconditions for a hunt were present in Finland as well.

Also in Finland, there were stories of witches’ sabbaths, where those allied with the devil would fly – often on a goat – to Blåkulla to wreak havoc. Evidence of witchcraft could include economic losses suffered by neighbours, such as dead cattle or people falling ill.

Controlling rumours and avoiding persecution is important even today.

Professor Raisa Toivo

The battle between good and evil was a real part of people’s worldview at the time. However, the policy of the developing legal system was that accusations had to be proven and could not be based on rumours.

“You can see in the sources how different parties deliberately made efforts to control the rumours. If a trial could not be avoided, at least unchecked persecution was prevented. For example, priests would bring cases to court, but at the same time, they would preach against bearing false witness against one’s neighbour,” Toivo points out.

According to Professor Toivo, death sentences as a punishment for witchcraft were really rare in Finland relative to the number of cases. The Court of Appeal often mitigated the lower courts’ sentences. Toivo urges us to consider the difficult situation faced by a close-knit village community when a lenient or rumour-quashing decision was made. The accused and the accusers still had to continue their daily lives as neighbours.

“In modern enemy group rhetoric, there is a similarity in how the target groups are depicted as causing all manner of evil. If persecutions could be avoided in the past, do we not also have the means to avoid them today?”

“The history of witch trials tells us where persecution originates, but also how it can be avoided. This is very important knowledge even in modern times,” Toivo reminds us.

Photo: Jonne Renvall/Tampereen yliopisto

Photo: Jonne Renvall/Tampereen yliopistoTemporal distance can enrich our view of history

Toivo believes that the early modern period provides temporal distance. The past is a foreign world where modern people do not need to be under direct scrutiny. Yet the past allows us to recognise the sore points of our own time and offers guidelines for avoiding polarisation.

Although deliberately distorted views of history exist and are sometimes invoked, Professor Toivo views interest in history positively.

“Different perspectives on the more distant past are certainly more readily accepted than on recent history. Once a person sets free their perspective based on the early modern period, they may be able to discuss recent history more openly, too,” Professor Toivo reflects.

Professor Raisa Toivo

- Studies and teaches the history of early modern society (circa 1500–1800).

- Specialises in the history of experience, social history, lived faith, and religious conflicts.

- Leads the lived religion section of the Research Council of Finland-funded Centre of Excellence in the History of Experiences (HEX) and serves as Vice-Director of the Centre.

- She is currently leading a project on How did Finland manage to avoid witch hunts?: Action and experience in de-escalating persecution.

Read Raisa Toivo's thoughts on early modern history on experiences:

Toivo, R. M. (2023). Väärin koettu, eli kaukaisten vuosisatojen varoituksia kokemuksen historiasta. Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae, 2023(2), 102–119.

Author: Mikko Korhonen