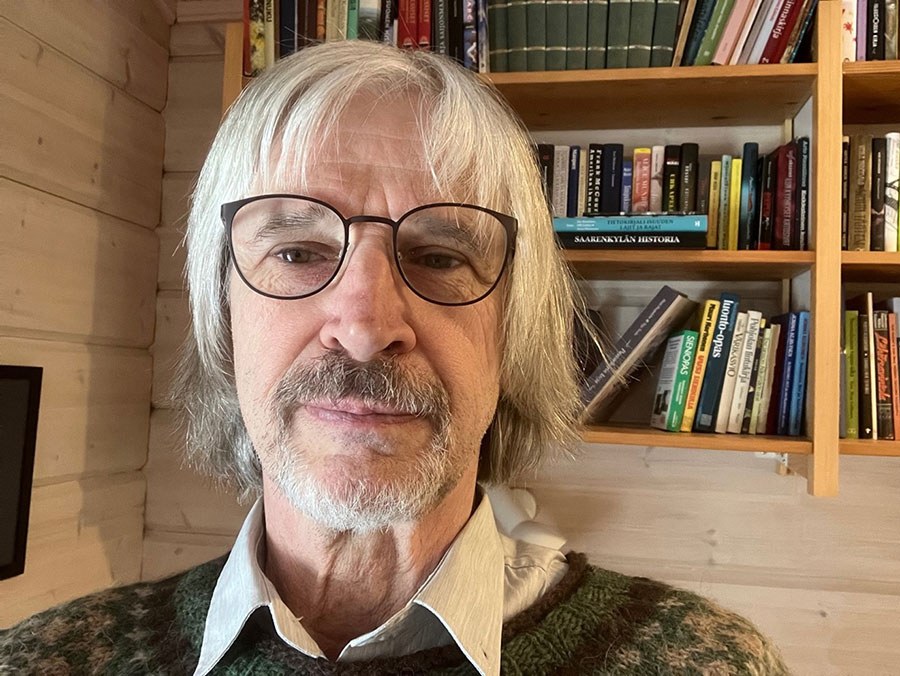

Sociologist Pertti Alasuutari shows how power is sanctified

Emeritus Professor Pertti Alasuutari argues that conformity – the ideal of similarity – is our way to seek recognition for the fact that we belong to the international community. His research group analysed this phenomenon through a sample of legislative proposals, using references to other countries as one indicator.

“Conformity also prevails more broadly in global organisation. We adhere to the same principles and standards that are often invoked to justify decisions. In a manner of speaking, similarity itself operates as a rationale. Something is, for instance, an international trend,” Alasuutari says.

In neoinstitutionalist sociology, organisations are examined as part of society. It researches established institutions, such as families, enterprises or ministries.

Professor Alasuutari introduced neoinstitutionalist sociological research at Tampere University. He launched a research seminar during his two terms as a Research Council of Finland-funded Academy Professor. Today, the Tampere research group for Cultural and Political Sociology (TCuPS), led by Alasuutari, continues this work.

The group also discussed chapters of Alasuutari’s recent book. Published by Oxford University Press, the volume brings together what Alasuutari and colleagues extensively researched during Alasuutari’s professorship: the organisational practices and functioning of parliaments.

“In Finland, nearly all political issues are raised in relation to some model. We speak, for example, of the Danish model and how we may apply it here,” Alasuutari notes.

The parliament was replicated worldwide

The parliament as an institution exemplifies this research tradition because it illustrates not only legislation but also external settings, work routines and even recurring rituals.

Alasuutari invites us to consider parliament buildings. They occupy central locations and fly national symbols on their flagpoles. From the perspective of routines, parliaments resemble law-making factories. The process – from policy papers through committees and subcommittees to voting – has been replicated in parliaments since the Second World War. Alasuutari describes this as a legislative ‘assembly line’ that produces laws and occasionally rejects proposals.

Alasuutari observes how the parliamentary model has been reproduced across UN member states since the Second World War in a surprisingly similar way.

His analysis extends to rituals, whether ceremonial, such as the processions in the British Parliament, or more mundane, such as linguistic conventions in the sessions. In Finland, for instance, an MP may not accuse a colleague of lying, but they may say that a colleague is telling ‘a modified truth’.

The nearest reference group of countries is strongly reflected in the justifications of decisions. Alasuutari says that through comparison with other countries and ritual practices, parliaments generate the emotional experience that political decisions are fair and appropriate.

“The parliament legitimises power. If the procedures were not observed, parliaments’ actions would lack a similar emotionally perceived efficacy,” Alasuutari concludes.

Democracy is never complete

Established practices reinforce the sense of democracy. Following the example of others serves the purpose of enabling each nation to profile itself as a member of the international community. However, problems arise when an authoritarian regime equates a parliament operating according to international models with the notion that its leaders are committed to democracy.

Alasuutari stresses that emphasising the role of parliaments in sanctifying power does not call their functioning into question. In his view, a well-functioning parliamentary democracy is a sound form of governance. To underline his point, Alasuutari cites philosopher Jacques Derrida, emphasising that democracy must always be regarded as something yet to come, never as the product of a finished model.

“It is better to think that the world is never complete. If external models are merely accepted as they are and it is assumed that they will generate democracy, the question of whether people can genuinely influence matters may be overlooked. In that case, the demand for democracy is discarded,” he says.

An emeritus sociologist of contemporary world

At the end of his tenure, Alasuutari gave a series of farewell lectures. Each lecture addressed a concept he considered central to society, research or his own thinking.

“I thought of giving the book compiled of these lectures the title Sociology of the Contemporary World. Society cannot be equated with a single country; it is a larger entity. The social system is a global-level phenomenon. Thus, I practise sociology that can grasp this global world.”

In retirement, Pertti Alasuutari continues to research electric vehicles sociologically.

“The transition from combustion engines to electric motors is part of a global effort to mitigate climate change. It is, and will remain, a massive infrastructural transformation worldwide, with implications for people’s lives and the organisation of societies. It would be almost absurd not to examine this phenomenon from a societal perspective.”

Alasuutari views the transition as driven by political decisions. Decisions were made within UN-affiliated organisations, particularly at the Kyoto conference in 1997.

“The narrative of technological development often omits that without political decisions this shift would never have begun. Those decisions gave engineers a reason to start developing batteries. There is also an economic dimension: how to make this a viable business and how people’s behaviour changes. Attention must be paid to multiple intersecting aspects of reality.”

In retirement, Alasuutari has also promoted the status of retired professors within the university community. He emphasises their role as researchers and supervisors – as full members of the academic community.

Publication:

Pertti Alasuutari, National Parliaments as a Global Institution: An Institutionalist View. Oxford University Press (2025).

Author: Mikko Korhonen