Novel human-derived cell culture models help to understand brain inflammation in multiple sclerosis

The symptoms of MS are driven by neurodegeneration and inflammation, but their complex mechanisms are poorly understood. To find the correct treatments for the inflammation smouldering in the central nervous system, it is essential to understand the nerve-supporting cells – astrocytes and microglia – that regulate inflammatory reactions in the brain. Currently, little is known about the behaviour and interaction of these cell types in MS.

Recent research findings from Sanna Hagman’s group, published in leading journals in the field, help to fill this gap. The team studied MS-like inflammation using human-derived cell models and demonstrated that microglia are more inflammatory in MS. This is a significant finding for the development of new treatments.

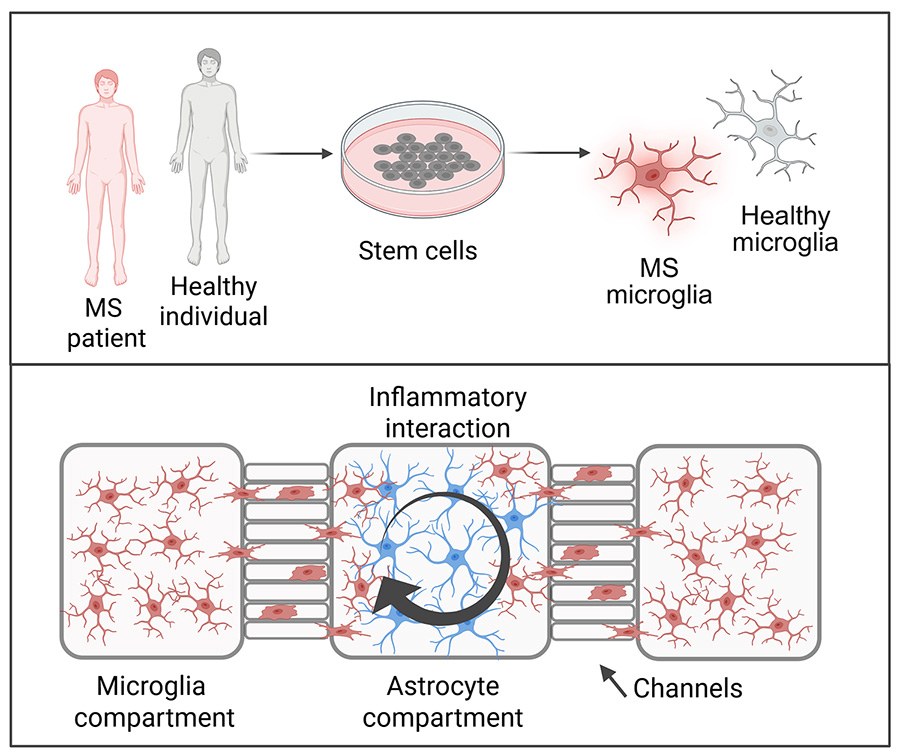

Doctoral researcher Iisa Tujula and colleagues examined the interaction between microglia and astrocytes in inflammation. They utilised a microfluidic chip whose chambers and channels allow the creation of different inflammatory environments and controlled interactions for the cells being studied. The researchers demonstrated that the interaction between astrocytes and microglia plays a key role in regulating brain inflammation.

“The results showed that there is a dynamic interplay between microglia and astrocytes. The cells regulate each other’s inflammatory activation and function by producing inflammatory molecules. Understanding this cellular communication may prove crucial for developing treatments for MS,” says Tujula.

Postdoctoral researcher Tanja Hyvärinen and doctoral researcher Johanna Tilvis used blood cells isolated from MS patients in their study. They reprogrammed these blood cells to become stem cells using iPS technology. The cells were then directed to differentiate into microglial cells. The researchers found that microglia derived from MS patients exhibited a heightened inflammatory profile compared to those from healthy individuals.

“Microglial cells differentiated from patients resemble the microglia found in MS inflammatory lesions and express more inflammation-related genes than healthy control cells. This finding suggests that MS patient-derived microglia may be more prone to inflammation, which could influence the course of the disease,” Hyvärinen explains.

Efficiency and tools for developing treatments

Traditional methods for studying the central nervous system largely rely on animal models. While they provide a wealth of valuable research data, the treatments based on them have a high failure rate in clinical trials due to the differences between human and animal species. Cell culture models based on human cells – so-called in vitro models – are therefore an important

complement to animal models and can also partly replace the use of animal models in research.

The Neuroimmunology Research Group has developed human cell models for MS in collaboration with national and international partners. The group has successfully produced patient-derived stem cell lines and differentiated them into desired cell types.

The research group also works closely with teams specialising in organ-on-a-chip technology, or tissue engineering. The closest collaborators are at Tampere University. For example, the microfluidic chip Tujula used in her study was developed by Professor Pasi Kallio’s and Adjunct Professor Susanna Narkilahti’s research groups.

The long-term goal of the Neuroimmunology Research Group is to develop and use cell culture models that are physiologically more relevant in MS-like inflammatory environments. The ultimate aim is to translate these findings into new research tools that will help develop treatments for the disease.

Iisa Tujula’s article Modeling neuroinflammatory interactions between microglia and astrocytes in a human iPSC-based coculture platform was published in the Cell Communication and Signaling journal. Read the article

Tanja Hyvärinen published her article Microglia from patients with multiple sclerosis display a cell-autonomous immune activation state in the Journal of Neuroinflammation. Read the article

The Research Council of Finland is the main funder of the research.