High-quality journalism does not feast on Covid-19 fears

This article was originally published in Unit, the magazine of Tampere Universities.

For news work, the corona pandemic is a tough opponent. The disease spreads rapidly, is inconspicuous at its mildest and deadly at worst. It offers both unsolicited hard news as well as twists, sacrifices, heroes, and villains worthy of an ancient rhetoric.

They are elements that, at best, give rise to insightful and high-quality journalism, and at worst, fear-inspiring voyeurism. There are no bad news days, but bad news abounds.

“The Finnish media has done a good job. There have only been few excesses,” says Janne Seppänen, professor of journalism at Tampere University.

Kari Koljonen, university lecturer in journalism who specialises in crisis journalism, agrees. Like Seppänen, he cites the largest Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat as a good example; it has removed the paywall from all its corona coverage. Other quality newspapers have not followed suit.

“Even in a state of emergency, news should not be made for free, but people are thirsting for information. If trusted media did not share information, we would mostly circulate rumours and social media feeds,” Koljonen says.

Yesterday’s infernos will be forgotten

Initially, the Finnish media covered the new disease, which had begun in China, with relative nonchalance. When the coronavirus arrived in Iran, the threat was understood, and the country was painted as a corona inferno. But when the disease reached Europe, Iran was almost forgotten, and the gaze shifted to the hubs of coronavirus in Italy and Austria. China had also begun to transform from a villain, which was likely to have triggered the crisis with its live animal markets, to a hero that consulted other nations.

News editors started to think how Finland would cope.

“One of the basic principles of news criteria is that the closer the crisis is in time, geography and culture, the more weight it gets,” Koljonen summarises.

The media are often rightly criticised for putting too much weight on things that are close by. “However, the coronavirus is a completely different news item than any previous crisis,” Koljonen says.

Now the same crisis is affecting every country in the world and threatening the lives of Finns.

Therefore, foreign news is also beginning to revolve around the idea of how Finland’s actions and destiny relate to other countries.

“The emergency measures are unique. It is understandable that in this situation, the news is mostly about the situation in Finland,” Koljonen notes.

Feasting on fear comes as a by-product

Dodgy reporting is also inevitable. Prominent examples are the cover headlines and stories of tabloid newspapers where single, voyeuristic horror stories are harnessed as the highlights of the day. Seppänen calls this phenomenon "corona porn".

“People are feasting on fear,” Seppänen summarises.

Feasting on fear is partly a conscious and commercial choice, partly a question of work culture.

“Tabloid newspapers are adept at digging up certain types of information even in normal conditions and appealing to the readers’ feelings. During this crisis, the same tools are also ready for use,” Koljonen notes.

The problem is that the news feeds of even some high-quality media unfold an infinitely sad picture about the events. As the pandemic spreads, more and more stories are being told about babies, children, or healthy young adults who have been in intensive care or succumbed to the disease and who were not supposed to be at risk.

“An exceptional story can be true in itself, but if the story is told, the journalists should have the ability to relate it to the context,” Koljonen says.

As the number of cases increases, the number of exceptional cases will inevitably increase even if the probabilities of the different forms of the disease remain the same. Reading about special cases collected centrally around the world distorts the overall picture and causes fear.

The media also present the numbers of patients and those in intensive care units well, but the number of those who have recovered receives much less attention.

The coronavirus outshines other scoops

The last time Finland lived in a state of emergency was during the war in 1945. War censorship limited what the citizens were told. During the corona crisis, Finns have been fairly unanimous about the state of emergency and the necessary restrictions. The opposition has been exceptionally weak.

A certain amount of self-control may also be observed in the media. In a democracy, the media must act as the watchdog of power, but in an emergency, the consensus is not easily shaken.

“Being the watchdog of democracy is the noblest task of journalism, but there are situations where public interest demands that you do not stir the pot too much,” Koljonen says.

Even in an emergency, the media still has the responsibility to question institutions and decision-makers because the public interest is served when they are required to act in the best possible way. However, at times, media have scraped through.

Seppänen would have liked to sharpen the discussion about the need for a special task force to handle the coronavirus situation, which President Niinistö proposed to Prime Minister Marin. For the most part, the discussion was stuck in the technicalities – it was not a matter of whether the overzealous uncle from Mäntyniemi stepped on the toes of the young mistress of Kesäranta.

“One can ask whether journalists would have dug deeper into this issue if we had not lived in such an exceptional situation,” Seppänen says.

“The crisis is over when the lead story is something else”

Seppänen thinks for a moment and manages to give one instruction to journalists from his armchair.

“I would suggest asking yourself one cynical question. Who benefits from the fact that the coronavirus is taking up all the space in the media?” he asks.

That would be those who would otherwise have to answer embarrassing questions more often than they do now.

At the end of March, Yle’s investigative journalism programme MOT revealed that in the €300 million renovation of the Helsinki Olympic Stadium, which is considered a national treasure, foreign labour had been exploited and threatened.

“In usual circumstances that would have been a big scandal, but now people were quite indifferent about it. Even if we did return to the issue later, that scoop has been burned out by now,” Seppänen says.

He believes that as the state of emergency continues, people will eventually get desensitised to the coronavirus. If society is to be opened, this previously unknown disease must begin to be accepted as just another cause of death among other illnesses.

“The media is a good indicator. The crisis is coming to an end when the leading stories increasingly begin to deal with something other than the virus,” Seppänen points out.

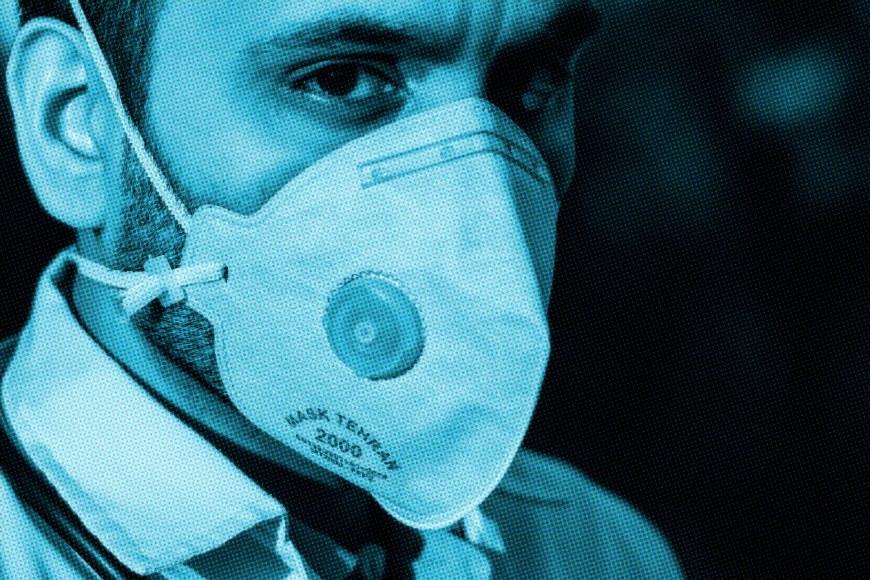

How to picture something you cannot see?

Most of the patients suffer the Covid-19 disease with mild symptoms at home, which is as it should be. However, that is bad from the perspective of illustration. An unusual image is the petrol of photojournalism.

Now, isolation is limiting photography, and pictures of self-isolating patients managing at home with fever medicines are nothing spectacular. The virus cannot be photographed, but a nurse who closely resembles an astronaut, is concrete and drastic as a visual representation. The corona imagery is created from the symbols of the virus.

“The way to visualise the coronavirus must be resolved. The nurses in protective gear give the message that this is a really bad thing and stay the hell away from us,” Seppänen notes.

Images can increase the scariness of the disease. At the same time, photographs have great power in how the crisis manifests itself as a social phenomenon. When thought positively, images can help justify restrictions, document everyday life, and highlight the hard work of important groups of people.

Iconic photographs will emerge later - such as Nick Út’s photograph of the girl injured by napalm in Vietnam (1972) or Nilüfer Demir’s photo of three-year-old Alan Kurdi who drowned in the Mediterranean (2015). They are easy to understand and symbolically summarise the spirit of an event or time. Iconicity takes time to be created.

“I have not yet seen a corresponding iconic image in the corona imagery yet, but one is sure to come. I strongly believe that that image will be related to the heroism of the nursing staff,” Seppänen says.

Author: Juho Paavola