Games offer interactive tools to cope with sustainability challenges

The course The Future at Play: Games for Sustainable Development (SDL640) focuses on how people can deal with and solve sustainability challenges through games and gamification. Such challenges can be, for example, climate change, responsible consumption and production, and clean energy.

“Through each interactive session, the students are introduced to specific sustainability topics, and are encouraged to discover, play, analyze and design games themselves. The course brings together two topical subjects and their interrelations: sustainability as a holistic and systemic approach to understanding environmental, social, and economic justice issues, and gamification, or the increasing prominence of games in multiple areas of society,” explains Ana Klock, a project researcher and one of the teachers on the course.

The course is taught by Gamification Group researchers.

Simulation games can help finding ways to cope with real-life challenges

As part of the active learning approach adopted, the teachers decided to kickstart the course with an online session of ’Possible World’, a sustainability simulation game created and facilitated by Imacocollabo. The game presents a virtual multiplayer world where each participant has a set of personal goals, and their actions affect the economic, social and environmental state of the world.

“This game aims at providing players with a first-person understanding of sustainability issues and the need to balance economic gains with social and environmental well-being, even if these realizations often come from failure,” states Georgina Guillen-Hanson, a doctoral researcher on games and gamification and another teacher of the course.

During the session, there were three player attitudes: 1) players that focused on their personal goals because, as one student put it during the game, “this is what the world is, nobody cares about others”, 2) players concerned about their personal goals to the point that they “forgot to focus on society”, and 3) players who overlooked their personal goals to focus exclusively on “saving the world.”

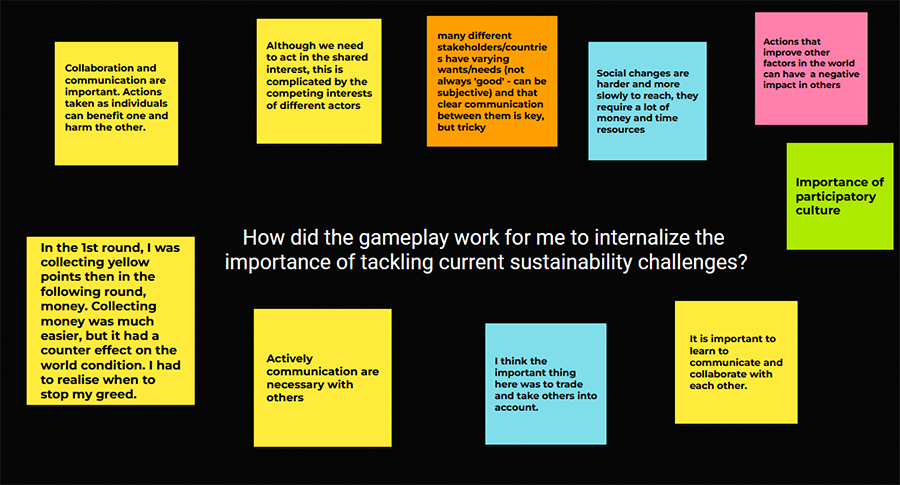

Overall, the simulated world did not develop in a balanced way. It had a booming economy, but society and environment were left facing serious challenges. This was attributed to “how easy it was to make money in comparison to protecting societies and ecosystems,” as one student put it, but also to the lack of “coordinated effort,” as analysed another.

Another student felt that the game was mirroring “a system whereby self-interest is incentivized and leads to collective harm” that required “consciously work[ing] against the default logic to win.”

Saving the world is not a piece of cake, but can succeed with cooperation

When players were given the opportunity to play again, they resolved to share more, communicate better and be more aware of other people’s and the world’s needs. Despite the good intentions the group failed to improve and preserve society and the environment in a good state.

In spite of the failures, students shared important reflections. Once again, collaboration was highlighted, although competing, individual goals challenge common goals. Another important outcome was the concept of tradeoffs, as progress in one area often involved losses in another.

“The game allowed players not only to understand the complexity of sustainability issues, but to experience it and come up with their own strategies,” sumps up Daniel Fernández Galeote, a teacher and doctoral researcher on games and gamification.

Basic and advanced understanding of sustainability

The game was adapted to the goals of the course and student reflections are brought up during the following sessions, both during traditional mentoring on sustainability and game concepts as well as in hands-on individual and group assignments.

“By using active learning and gamified methods, we aim to equally engage students with varying degrees of familiarity with sustainability. The game offers a broad understanding of sustainability for the beginners on the subject, and on the other hand, an insightful experience for more experienced ones,” says Fernández Galeote.

Playing, reflecting upon and creating games can be adapted to many other topics as well. These experiences, together with traditional teaching and critical discussion, hold great potential for education, citizen engagement and professional training.

“Currently, students are working on their game design group projects, and we expect that by the end of the course they will have a critical understanding of sustainability and the role games play in it,” he adds.

The interdisciplinary course is based on aspects of game research, environmental science, psychology, communication, and education. The course will take place again next year during the third period.

Further information

Daniel Fernández Galeote

daniel.fernandezgaleote [at] tuni.fi

Ana Klock

ana.tomeklock [at] tuni.fi

Ginnie Guillen-Hanson

georgina.guillen [at] tuni.fi