Entertainment is power. It sells us needs, ideas and concrete items. Vikings, knights and other “he-men” are used to advertize objects ranging from pickup trucks to condoms.

The Middle Ages is still present in its imaginary form. It is an imagined past we all share and recognize but which is safely far – it will not challenge or threaten our understanding of ourselves. Especially in this context, in creating ideas and modes of thought, the imagined past has become more and more important.

Seeing through the cloak of fantasy and entertainment, the Middle Ages seems quite harmless – everybody knows (well, all schoolchildren may no longer know) that dragons did really not exist or that Game of Thrones is not set in the medieval era. One needs to be devoid of humor to be irritated by harmless entertainment – right? Opinions vary whether harmless entertainment actually exists, because humor always – intentionally or unintentionally – reveals sore spots of society.

Entertainment is power. It sells us needs, ideas and concrete items. Vikings, knights and other “he-men” are used to advertize objects ranging from pickup trucks to condoms.

The problem with imagined masculinities of the past is the rigid idea of men and manhood it creates. The imagery of “medieval” men created by popular culture supports heteronormativity and, in the worst case, toxic masculinity. In other words, dragons are not the most dangerous thing that the (fictitious) Middle Ages brings forward.

It seems that the United States has a head start in the commercial exploitation of the Middle Ages. Probably medieval past is a particularly fertile soil because United States does not share it as a nation. It is thus an unlimited territory for exploitation, also for striving for politically questionable gains. The power and danger of a fictitious past reside primarily in images and thinking patterns that are indirectly used to consolidate existing cultural conceptions and categories. Captivating stories feed escapism and the longing for exoticism or mysticism. The modernized characters make the audience easily identify with their emotions, actions and destinies. Vikings and knights thus help in marketing the idea of real male, which is both psychically and physically strong and staunch, even aggressive and violent if need be. On the other hand, the hero can help the weaker ones. This thinking advertently or inadvertently confirms the “correct” gender order and the rigid image of masculinity. The problem with imagined masculinities of the past is the rigid idea of men and manhood it creates. The imagery of “medieval” men created by popular culture supports heteronormativity and, in the worst case, toxic masculinity. In other words, dragons are not the most dangerous thing that the (fictitious) Middle Ages brings forward.

The medieval ideal of masculinity was much more than or, as a matter of fact, something quite different from a muscular man stained with sweat and blood.

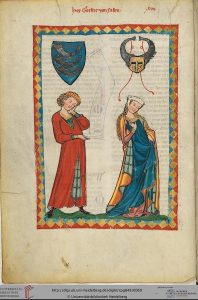

The medieval ideal of masculinity was much more than or, as a matter of fact, something quite different from a muscular man stained with sweat and blood. This can be observed in the poetry collection called Codex Manesse. This anthology of love songs and poetry compiled for the Manesse family reflects the German version of courtly love. The anthology consists of over 130 poems written between the 12th and 15th centuries, and its illustrations are made at the beginning of the 14th century. Each poet is depicted individually; they represent without doubt the elite, rulers and nobility of the time. In spite of – or because of – that they also reflect the ideal masculinity. Among the figures, there are also knights in their shining armors but especially conspicuous is the fact how beautiful, fragile or even feminine the male characters look. In a society built on manual labor, the ideal man was not a big bunch of muscles but a smooth-faced and slender youth with thin, even delicate, long limbs and pale skin. Both men and women strove for longish fair curls. External beauty was a sign of internal goodness, sinful people and evil spirits also looked disagreeable.

When, at the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Early Modern Era, the men’s capes became shorter, the hallmark of coveted masculinity was long, firm and beauteous legs, which were accentuated by garters under the knee. King Edward III of England even founded the Order of the Garter in 1340s. It is the oldest and most esteemed of the orders still functioning in England. At the beginning of the Early Modern Era there were also calf implants available for those not having sufficient natural curves. Long, delicate but still voluptuous legs are thus a centuries old beauty ideal and sexual attribute – nowadays they are, however, more often linked to female beauty.

The attraction of sexual performance was known in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Era. When capes were short and trousers or stockings had two parts, modesty required a codpiece. It became soon an advertizement of masculinity and prowess. In portraits this accessory is often enhanced, padded and decorated. It accentuated sexual capability as well as fertility.

The form and function of a codpiece is thus not very far from today’s push-up bra. It both emphasized and hid genitals; its ambiguousness was amplified by its artificiality, futility and vanity – elements that were associated primarily with femininity during the golden era of codpieces. Besides male prowess the codpiece also symbolized other cultural values. Its message was linked to the importance of the family and dynasty relationships.

In the Late Middle Ages, the continuity of the dynasty became more and more important also for the bourgeoisie, and this was reflected in clothes, sepulchral monuments and the selection of a patron saint. The feminine counterpart accentuating fertility was probably a fashionable skirt that was piled up over the abdomen to resemble pregnancy. The codpiece has not disappeared in history in the same way as calf implants but now belongs to the apparel of some heavy metal bands. The replicas of clothes from the Late Middle Ages thus tell us something about today’s masculinity as well. I will leave it up to the reader whether the symbolic significance is still resonating with family values.

The images of medieval masculine men created by the entertainment industry may well correspond to our own ideals and demands.

The ideal of a masculine appearance is neither stable nor invariable. The images of medieval men created by the entertainment industry may well correspond to our own ideals and demands. Appearance as a way to create and manifest status and prestige is a shared element of both eras, but ideals fluctuate according to the context.

Although Codex Manesse contains figures of smooth-skinned young men, the more general male ideal of the Middle Ages was a bearded patriarch of mature age. The facial hair told the difference between a man and a boy. The beard was a status marker also in a different sense: the ecclesiastical statutes forbade clergymen from growing a beard because a clean-shaved face – like a tonsure – was a symbol of chastity and humility. The beard is a visible and easily fashioned expression of gender and can be used to signal religion and other societal opinions. These hairy messages can be based on the owner’s aspirations or external control.