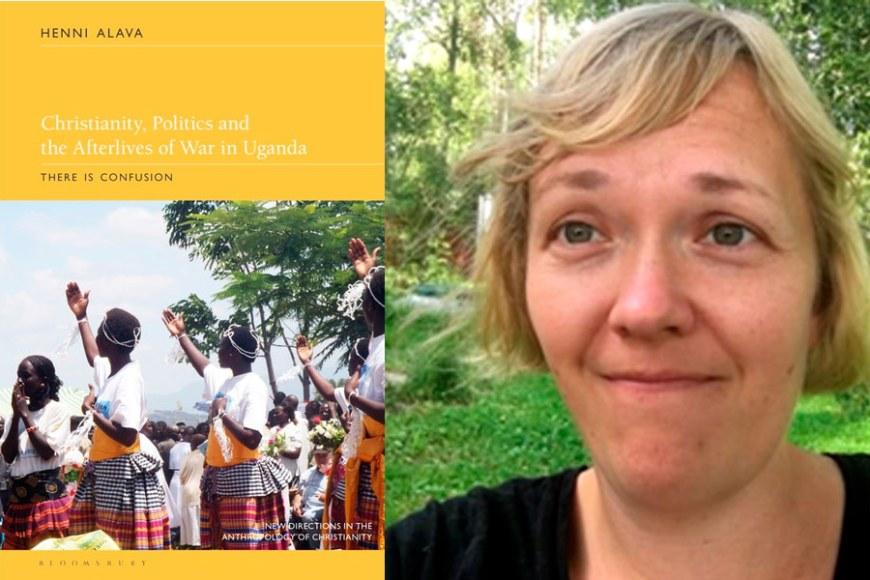

Henni Alava’s acclaimed research combines critique with a message of hope

Academy Research Fellow Henni Alava from Tampere University began her research in northern Uganda amidst a major humanitarian disaster toward the end of a 20-year-long conflict.

The Society for the Anthropology of Religion, a chapter of the American Anthropological Association, awarded Alava with an Honorable Mention of the Clifford Geertz Book Award in 2023.

In her thanks, Alava highlighted Uganda’s serious human rights situation. She also called attention to the hope that runs through her research.

“As social scientists we must balance between social critique on one hand and hope on the other. We need both. A researcher may write critically about suffering and problems while also taking account of even the tiniest efforts to strive for the good,” Alava says.

Alava believes her research offers perspectives on how we approach crises. How the Ugandans she worked with in the northern part of the country coped with difficulties witnessed both pragmatic adaptation and holding on to that which is good. Life must go on even in difficult times. “Only very privileged people have the chance to wallow in despair,” she says.

Embedded religion and politics

Alava describes her approach as a political anthropology of Christianity, where religion and politics are analysed simultaneously.

“The idea of politics and religion as separate leads us to analyse them separately. Yet even in Finland, Lutheran ideas about human value or the place of people resonate behind political decisions. Religion and spirituality have a bearing on worldviews,” Alava points out.

In her research, Alava combines concepts from, for instance, African theology, anthropology, utopian studies, and political science. They all provide her tools for studying social change.

In her new book, Alava analyses, for example, political events that are carried out in a church context. Church services, a church choir and prayer can be studied as rituals that shape communities’ understanding of who belongs to a political community, to ‘us’.

A choir as a way to unpack war traumas

Alongside studying the role of churches in the reconstruction of northern Uganda, Alava observed how individual people orientate towards society in the aftermath of war. Political agency is evident in both formal politics and at different levels of community, of which Alava uses a church choir as an example.

By participating in the choir’s rehearsals, performances and the everyday lives of choir members, Alava gained insight into the ways people deal with war trauma and relate to institutions such as the church and the state. Since choir rehearsals consisted of singing alongside chit chat, an anthropologist could observe what is said publicly and what is left unsaid. Alava also found it insightful to witness how the choir approached public authorities when performing for them.

The Anglican choir studied by Alava practiced old Anglican hymns both in the local Acholi and in English six days a week. The composition of the choir cut across all social classes from the unemployed to local elites. The choir also supported members at times of adversity.

“Western-centric post-conflict interventions often emphasise the importance of talking for healing. In northern Uganda, my observation was that people did not want to talk to outsiders or often to each other about the things they had experienced during the war,” Alava points out.

“Most Ugandans I know recover from trauma quietly, in everyday life. People are not interested in sitting in therapy sessions, and even if they were, therapies are not available. Instead, recovery takes place through singing, praying, cultivating the land, raising children: by living your life because there is nothing else you can do,” Alava says.

Churches paradoxically respected both peacemakers and moral critics

According to Alava, the moral codes being pushed through in Uganda, for example, in the recently passed harsh anti-homosexuality legislation, do not tell the whole story about how ordinary Ugandans think about matters of morality.

In northern Uganda, churches enjoy significant respect for their role as peacemakers during and in the aftermath of the war. At the same time, the way churches talk about people belonging to, for example, sexual minorities, builds boundaries of exclusion in society.

“Even though churches in Uganda are major sources of moral indignation, not all Ugandans take the churches’ teachings at face value. For instance, polygamy still occurs, or people do not marry at all, even though the churches emphasise the importance of church weddings,” Alava says.

The conflict between the churches’ work for peace work and their connection to violence has ended up in the subtitle of Alava’s book. “There is confusion” — “anyobanyoba tye” in Acholi— is a sigh used by many northern Ugandans when things are confusing or contradictory.

Analysing the choir shows both these aspects and elucidates how moralistic discrimination affects everyday life. In the events where the choir performs, sermons may highlight the value of marriage, and shame single parents for being unwed.

“Yet approximately half of the choir members are single parents, including many mothers whose child’s father refused to marry them for one reason or another. Despite this, the choir members went to perform at church events, and constantly voluntarily exposed themselves to disapproval. In private, many told me how much such sermons hurt them, and how annoyed they were by what they saw as the church’s double standards,” Alava explains.

“However, none of them ever spoke publicly about the matter. What they gained from their faith, and from attending choir practice, outweighed the pain caused by the criticism,” she adds.

Henni Alava: Christianity, Politics and the Afterlives of War in Uganda. There is Confusion. Bloomsbury (2023).

The book’s Open Access version

The Clifford Geertz Prize (Society for the Anthropology of Religion)