If you’ve ever played an open, exploration-heavy game, you might be intimately familiar with the following scenario: you’re looking around, orienting yourself in the terrain, and you notice that far down below you, in an area you never expected to be able to reach, there’s the familiar glow of a collectible item. Unbounded by the confines of a detailed map, the game’s world seems only as big as your experience of it, and suddenly your expectations have expanded. If I can get to those distant rooftops, you might ask, then where else can I go?

Daniel Vella, a games researcher from the University of Malta, calls this an experience of the ludic sublime. He uses Dark Souls, a game which gives you no map and only vague objectives, as his primary example of the phenomenon. Taken from the greater meaning of sublime as something boundless and unknowable, the ludic sublime describes a particular tension between mastery and mystery. As you play a game, you’re building up a sense of its world, its mechanics, its whole “phenomenal cosmos,” and trying to understand and master these systems. At the same time, thanks to how games are structured as a medium, it’s impossible to grasp a full sense of a game system without picking apart the code yourself. When a game makes you realize how little you understand about it—when it creates a sense of mystery by hinting at its own depths—that’s the ludic sublime.

The Dark Souls example above, in which a game blurs the boundaries between in-bounds and out-of-bounds (“ludic and extra-ludic space”) and converts I can’t go there into I can’t go there YET, is only one type of design that can create a sense of the sublime. Dark Souls veterans will likely remember the obtuse humanity system, a core mechanic that never quite explains itself. This too is another kind of hint that the game system may be far deeper than a player’s present understanding can account for. Playing a game like Dark Souls without help from online tutorials or other players, you can imagine stumbling across some secret mechanical interaction that makes you question how many other similar ones you’re missing. The obtuse, unintuitive questline that lets you save Solaire, for example, has so little in-game indication of the possibility of pursuing it that it invites this sort of speculation. On the other hand, entities with no clear function can provoke suspicion: if the mysterious Peculiar Doll can turn out to be a key, might the same be true of the Pendant, an item described as having “no effect”?

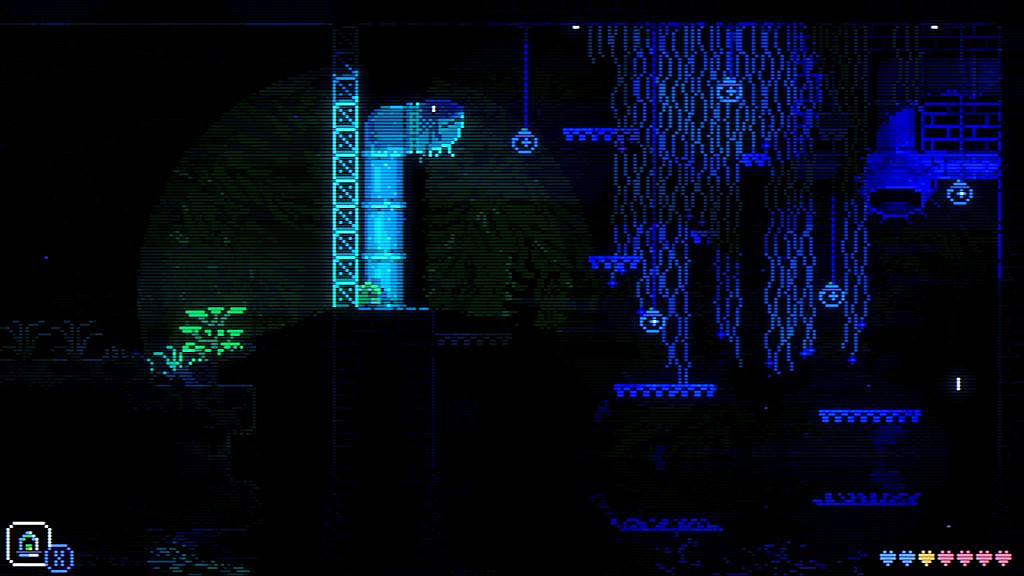

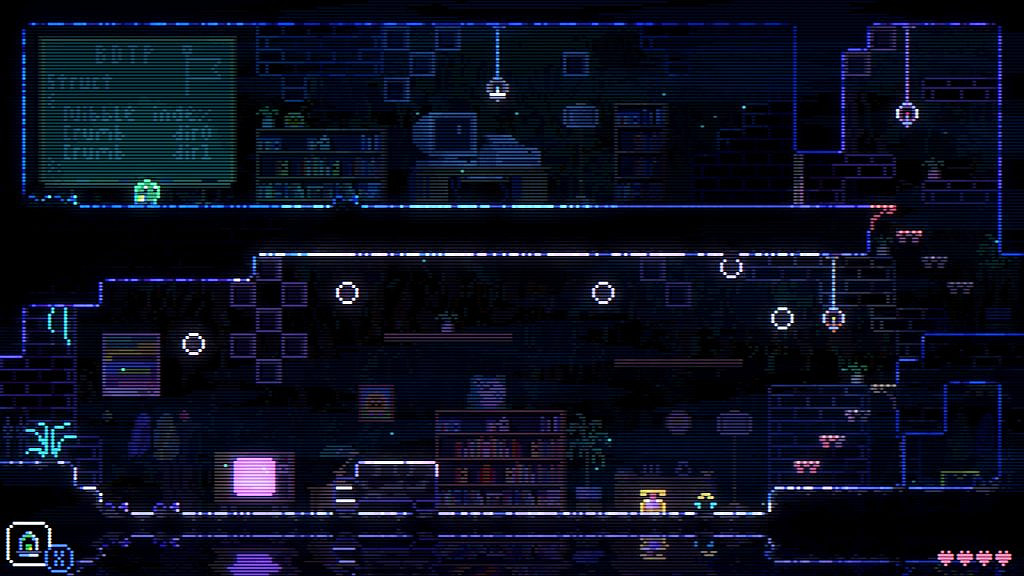

Once you recognize the telltale markings of the ludic sublime, you start to realize how central this affect is to a certain sort of mystery-oriented game. Animal Well, a critically-acclaimed, exploration-focused puzzle-metroidvania from last year, is one recent title whose ridiculous depths might be taken as new expressions of the ludic sublime. Its Steam description concludes with the sentence “There is more than what you see,” and it certainly delivers on that promise: fans of Animal Well speak of at least four distinct “layers” to the game, discovered as you journey further and further “down the well” of secrets. These layers foreshadow each other by reminding you, to use Vella’s term, of the partiality of your own experience: rooms you can’t enter, glyphs you can’t decipher, collectibles (especially the enigmatic bunnies that appear after difficult challenges) that at first seem to have no purpose. Once you realize how many barely-visible background objects form parts of complex puzzles three layers in, you might be overwhelmed with the possibilities. Does everything have significance? How many more secret rooms will open up to you if you just search hard enough?

Vella’s paper was published in 2015, before the widespread availability of tools to pick apart games and gain complete knowledge of their systems. As it turns out, secret-seekers on Reddit were able to plumb the entire depths of Animal Well’s source code—a considerable feat, given that the developer actively tried to circumvent datamining—in about a week. Certainly, Vella’s claim that players can only ever asymptotically approach the full truth of a game now seems outdated. But this doesn’t mean that we should do away with the ludic sublime. It is still an insightful way to think about how games create mystery for their players. And knowledge of source code doesn’t mean the mystery is gone: though dataminers had cracked Animal Well’s final puzzles, it took players much longer to discover the intended solutions. Despite the internet’s collective knowledge, it is still, I think, possible to imagine—through symbolism, backstory, and other textual mysteries—new sublime depths to the well.

Basic information:

Source: Vella, D. (2015). No Mastery Without Mystery: Dark Souls and the Ludic Sublime. Game Studies, 15(1). https://gamestudies.org/1501/articles/vella

Photos:

Screenshots taken by the author from Dark Souls Remastered (FromSoftware, Inc. 2018) and Animal Well (Billy Basso 2024).